For or against self-service scooters? That's the question Parisians will be asked to vote on the 2nd of April. After enjoying considerable success in the United States, free-floating or self-service electric scooters (note that there are no mechanical scooters) arrived in the French capital in 2018 [1]. Thanks to a fast-paced development model, they now dominate the urban micromobility market alongside self-service bicycles and have brought radical changes in travel habits in just a few years. However, these fleets of scooters have come in for a great deal of criticism from some residents, who accuse them of being a danger to other public space users, of cluttering up public space and of encouraging passivity when it comes to getting around. This has led to the introduction of regulations governing these fleets, particularly in terms of parking and maximum speed (in Paris, the authorized limit for these machines is 10 km/h, and even 20 km/h on certain major roads), in order to contain the nuisance and the number of traffic accidents.

Alongside these issues of urban mobility, are scooters helping to decarbonize cities?

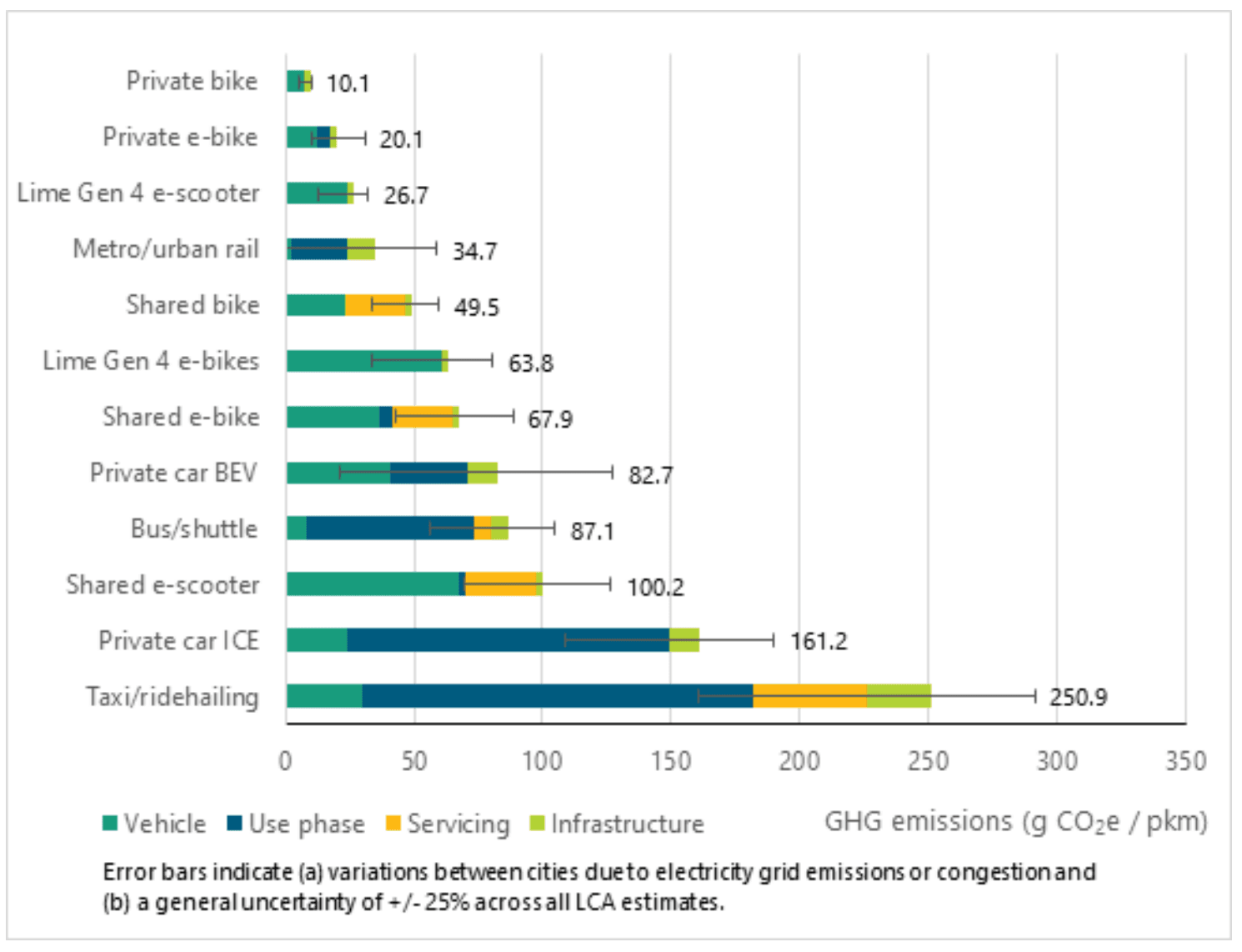

Electric scooters are one of the least carbon-intensive forms of urban mobility during utilization, apart from active forms of mobility such as walking, mechanical cycling and even... mechanical scooters!

However, if we look at the carbon lifecycle of a self-service scooter, including the manufacturing footprint, the impact varies greatly depending on the city and the lifespan of the scooter, which can be very short, which has a negative impact on its overall carbon footprint. The Fraunhofer ISI study [2] published in 2022 considered the impact of the scooter fleet of the American company Lime, which owns a third of the self-service fleet in Paris. Considering not only use, but also infrastructure, the manufacture of the electric scooter and its maintenance, the carbon impact according to Fraunhofer ISI is 27 gCO2e per passenger and per kilometer on average. This makes it less carbon-intensive than a car, whether combustion-powered or electric, but more than the metro (in France, where electricity is largely decarbonized), cycling or walking.

The question of modal shift, i.e., what the electric scooter replaces, is therefore crucial. However, this does not work in its favor.

Again, according to the Fraunhofer ISI study, the modal shift varies greatly depending on the city and its public transport network. In the case of Paris, the Fraunhofer ISI study shows that 40% of journeys made with an electric scooter replace walking, 30% the metro, 9% taxis/VTCs, 7% bicycles (self-service or not), 5% buses, and 5% cars or motorbikes (electric and internal combustion). In 77% of cases (walking, metro, cycling), electric scooters replace active modes of transport, which in most cases are less carbon intensive.

However, as scooters remain a low-carbon mode of transport, when we look at the differences in emissions according to the modes of transport replaced, electric scooters reduce emissions by an average of 21 gCO2 e/passenger.km, because even with a low modal shift, cars and motorbikes are much more emissive.

Looking ahead to low-carbon cities, self-service electric scooters may well have their place as low-emission, lightweight vehicles that take up relatively little space and make little noise. However, this is not the preferred option, as active modes such as walking or cycling are less carbon-intensive, consume less energy and critical metals (as there are no batteries), and are a key factor in maintaining good health.

The future of the 15,000 self-service scooters currently operating in Paris is uncertain, and the vote goes beyond the simple carbon aspect, but whatever the result, boosting the role of active modes of transport in our cities is a lever that must remain a priority.

Contact us

Contact us about any question you have about Carbone 4, or for a request for specific assistance.